Date£º

2014-10-08 11:16 Source£º

winesearcher Author:

Translator:

Mike Steinberger doubts that mandatory ingredient lists on wine labels would alter anything about how those wines are made.

Fotolia | There is a growing trend to evaluate wine by how the label says it's made rather than how it tastes

Amid all the debate these days about authenticity in wine -what it means and how to achieve it -one idea in particular seems to be gaining traction: full disclosure on labels.

Those championing this idea believe that, with so many additives and technological fixes now available to winemakers, the sparsely worded labels that are the industry standard are no longer acceptable; producers should instead provide as much detail as possible about how their wines were made.

Did they use ambient yeasts or inoculated ones? Was the wine chaptalized or acidified? How much sulfur was used? The argument is straightforward: in the same way that consumers are entitled to know what goes into the foods they eat, they are entitled to know what goes into the wines that they drink, and winemakers have an obligation to provide them with this information.

As both a journalist and as a wine enthusiast, I'm all for greater transparency. Given a choice between less information or more, I'll always opt for more (though that may soon change; my son just turned 13, and as we endure the teenage years, I suspect there will be some things that I don't wish to know about). But allow me a moment of devil's advocacy; while full disclosure on labels (or as much disclosure as a standard wine label will permit) is a laudable goal, there are a few sticking points worth acknowledging.

To begin with, the comparison with food is misguided. Unlike food, wine is not necessary for sustenance (it only seems that way), so the need-to-know argument does not carry nearly the same weight. More importantly, there is no evidence that any of the various additives that have become popular bogeymen ?Mega Purple, gum arabic, powdered tannins ?pose a health risk to wine consumers.

Some proponents of natural wines contend that "industrial" wines are bad for us, but they are trafficking in fear-mongering, not science. The case against these additives is purely aesthetic; they can't poison our bodies, they merely offend our sensibilities.

For these reasons, it is highly unlikely that full-disclosure labeling is ever going to be made mandatory, nor should it be.

As a result, the only winemakers likely to offer a full list of ingredients on their labels are those whose vineyard and cellar protocols are considered virtuous by the wine intelligentsia. Presumably, proponents of full disclosure believe that if enough producers adopt the practice, it will shame the holdouts into following suit. But that's probably wishful thinking. Here's the thing: the people who want full disclosure on labels generally don't drink the kinds of wines that are made with lots of additives and with all sorts of high-tech fixes; conversely, the people who do drink those kinds of wines probably don't much care how they are made.

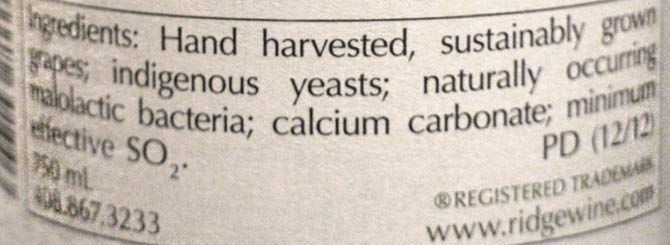

?Ridge Vineyards | At the forefront of moves to greater transparency on labels, Ridge Vineyards' back label lists ingredients

Ingredient listings have done little to discourage consumers from eating highly processed foods; it is doubtful that the millions of people who happily toss back highly processed wines are suddenly going to demand to know if enzymes have been added to their favorite Cabernet. In the absence of government-mandated labeling or a groundswell of popular support for the idea, wineries that use things like Mega Purple are not likely to feel any pressing need to own up to these practices.

There's another reason to be wary of full-disclosure labeling: it is only going to encourage one of the more regrettable trends of recent times. The past few years have seen the advent of a new breed of label drinker ?one who prejudges wines based on alcohol levels and oak regime. If the alcohol level of a wine is above a certain, arbitrary threshold, and/or if the wine was matured mainly or exclusively in new oak, these label drinkers are predisposed to dislike it. And, with the rise of the natural wine movement, we've seen the emergence of an entire subgroup of enophiles who appear to assess wines based in part or entirely on how they were produced ("tell me how it was made, I'll tell you what I think of it").

It seems to me that full-disclosure labeling would mostly be a sop to these process-oriented types, who are inclined to evaluate wines based on how they were made. A few years ago, Ridge Vineyards, which is at the forefront of the effort to promote greater transparency, noted on the label of one of its Zinfandels that water had been added to the wine; at harvest, some of the fruit was overripe, so Ridge resorted to "Jesus units" to bring the Zinfandel into greater balance. There are wine writers and wine enthusiasts who, on seeing that information, would immediately dismiss the wine, surmising that the Ridge folks messed up in the vineyard and had to add water back to compensate for the overripe fruit ?therefore the wine would be flawed. Their perception of the wine would be tainted by the knowledge that the vinification process included a step that they frown upon.

I'm not suggesting Ridge should have withheld that information; I applaud the winery's candor, and again, I'm all for transparency.

My point is simply this: if the push for ingredient labeling is intended to smoke out the worst offenders ?that is those producers who load their wines with additives and use all sorts of technological crutches ?then it's not likely to succeed.

I suspect the main effect of full-disclosure labeling, if the idea gains any real traction, will simply be to reinforce the tendency of certain enophiles to judge wines according to how they were made. That's not a reason to oppose full-disclosure labeling, but it's probably fantasy to believe that ingredient lists are going to somehow discourage the use of things like gum arabic and powdered tannins. It hasn't happened with food; I doubt it will happen with wine.